|

|

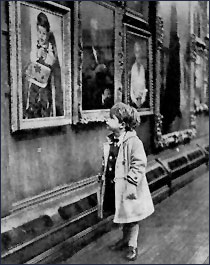

About [Scottish Field: article by T J Honeyman. August 1955]An artist with a very personal and pronounced outlook, best known for his paintings of children. For some time now I have been going out of my way to investigate the oft-repeated assertion that private patronage of the arts is a thing of the past. Many older people who are interested in the arts deplore the fact that in Scotland to-day we do not have the same number of collectors. They used to fill their homes with paintings of all sorts and sizes. People with money spent a lot of it on pictures. And there were more whole-time artists in Scotland; men and women, who were able to devote their energies exclusively to the job of producing works of art. To-day, the majority of our artists, for economic reasons, are compelled to spend far too much of their time in teaching. And it is not until in later in life they may receive sufficient inducement to take their courage in their own hands. In my view, the situation is not as gloomy or as hopeless as it is often made out to be. Apart altogether from other considerations, the time is still very far distant when we can rely on either the state or the municipality becoming the patrons of the arts. I am aware of a vitality among the Scots artists of to-day. It warrants a much higher place in British art than has up to now been conceded. What is required is a dignified and persistent propaganda to tell the world more about ourselves. For instance, it is not too much to say that propaganda helped the genius of Bone, Cameron and McBey to achieve recognition as three great modern masters of engraving. The same applies with equal force to the famous Glasgow School. The fame achieved by the school on the Continent and in America was in the first instance created by the then up-to-date methods in publicity. The artist who sulks in his studio and consoles himself with the stimulating thought that posterity will appreciate him is calculating too much on history repeating itself. So long as there are four to five million in Scotland, there are patrons of the arts. They are only buried and we have to dig them out. Until Scotland is able and willing to support its own sons and daughters who have surrendered to the overwhelming urge to express themselves in some art form – music, painting or drama – the search for support must be continued beyond the national boundaries. And it does not matter very much if an Englishman or a Frenchman is the first to tell us that we have bred a genius. Moreover, if our exiled Scots, for sentimental or other reasons choose to become interested in the home product, they can do us a great service by making us feel that we ought to be ashamed of ourselves. This is again the day of the individual in art. If he is one of a group, he is so mainly for the stimulus of agreeable company. It is the vigour of personality that marks contemporary Scots art. We are being shown in our exhibitions to-day that pictures and sculptures are more than decorations. I think, too, that our artists are proving that the boast, “We are not an emotional people,” is an absurdity. One of the most independent of Scots artists is Archibald McGlashan, R.S.A. I have known him for a long time and it is interesting for me to recall two sentences I wrote about him nearly twenty years ago. “Here is a man who has never in the least been ambitious for academic honours nor complained when these have been tardily bestowed. He has no ostentation, no feelings of envy or hatred; his philosophy is that of getting on with the job of work to be done, hoping that sometimes it may be lucrative enough to supply the necessaries of life.” Nothing has happened in the intervening years to lead me to want to change that. According to some, he is still needlessly stubborn in refusing to conform to what the public wants and in his resistance to the allure of easy money. It must have dawned on McGlashan early in his career that art demands exclusive sacrifice. It requires from its devotees the consecration of their entire existence, all their intellect and all their labour. I am proud to be among those who salute him for his loyalty and his integrity. Archibald McGlashan was born in Paisley and is now in his middle sixties. He had his basic art training at the Glasgow Art School, where his principal teacher was Maurice Greiffenhagen, who, along with the Director, Fra H Newbery, exercised a profound and abiding influence on their students, to the great advantage of most of them. Among other prizes, McGlashan won a travelling scholarship which it made it possible for him to visit Spain and Italy. In 1913 he spent six months in Madrid copying Velasquez, El Greco and Titian. He became aware of how much Spain owed to Italy. This discovery compelled him to continue his studies of the great Italian painters in their own country. To speak of influences in any artist’s work is to do nothing more than indicate a starting point. And it is clear that McGlashan’s starting is to be found among the Italian masters. He has told me that he understood the French “moderns” although he never attempted to paint like them as was the custom among most his contemporaries. This was not because he adopted a detached or superior point of view. He was well aware of the fact that the theory and practice of French art from Impressionism onwards had become fused with the general trends of European painting. But a disciple need not be a slave. At this time his independence of view marked him out as something out of the ordinary run of development in Scottish art. He was not altogether an isolated figure. Looking back, I associate with him Robert Sivell and James Cowie. Unlike their fellow students, these three seemed to stand out as a rebel band who refused to swear allegiance to France. The “Auld Alliance” was all very well, but they preferred to build on the foundations established by the Renaissance masters. I recollect a mild furore in Glasgow Art Circles when in the late ‘twenties The Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts rejected two paintings, one by Sivell and the other by McGlashan. They were important works and each of the artists regarded them as among the finest they had ever produced. This view I shared and arranged for them to be exhibited in Alex. Reid’s Gallery. Sivell and Cowie elected to go in for teaching: they had probably found a degree of interest in the schools. Each of them has exercised a very sound influence on their succeeding generation. McGlashan persevered with the struggle, experiencing many disappointments and, sometimes, privation. At times he was seriously temped to accept a commercial post, newspaper work, etc. However, he felt that it was essential for him to retain his independence and continue the fight until recognition came. Those who knew him and his work were quite confident that in due time he would make the grade and become a notable representative of the west in the age-long competition with the east. Unfortunately, those who know are seldom those who are able to buy, and a man needs more than the faith and devotion of brother artists to sustain himself. It is necessary to have models. But models cost money. It is not unlikely that McGlashan’s brilliant early sketches of his own babies were responsible for a sustained interest in infants and young children as material for picture-making. One very fine self-portrait was probably started because his wife had rebelled at the constant demands on her young family. At any rate, I choose to think that these pictures of sleeping babies, exemplifying the beginning of McGlashan’s most notable and enduring work made all of us aware of an artist with a very personal and pronounced outlook. He may quarrel with the description, but I believe it is competent to describe him as a specialist in children’s portraiture. That does not imply deficiencies when it comes to his performances in adult portraiture. It certainly defines the nature of public appreciation and the circumstance of the larger part of his commissioned work. What may be described as his London period started in this way. To keep the pot boiling, I persuaded a friend of mine, Dr James Harper, a well-known Glasgow surgeon, to allow McGlashan to experiment with a portrait of one of his sons. The boy was painted in the bright red blazer of Loretto School. I doubt very much if the finished result met with the unanimous approval of the family, but among McGlashan’s friends, including myself, it was accepted as a strikingly effective piece of portraiture. We managed to get it included in an exhibition in London, where it created a mild sensation. I was particularly pleased to hear the reactions of several well-known London artists, including Duncan Grant and Ethel Walker. They praised it in most generous terms. One thing led to another and I was able to persuade McGlashan to come to London for a spell. While waiting for things to happen he did a portrait of our daughter and the son of my partner, McNeill Reid. These two were exhibited, and a series of commissions followed. Most of these were of children of well-known public figures. Some members of the theatrical profession became interested, and McGlashan did a number of their portraits. Many of these were actually done in dressing rooms, between the acts, whenever and wherever a sitting could be arranged. He had the good fortune to win the appreciation and respect of Sir Edward Marsh, celebrated, among other things, as a most persistent first-nighter. McGlashan’s portrait of Sir Edward, reproduced in colour in a prominent art magazine, led to much controversial discussion. It may have been a little too penetrating. Irrespective of the views of relatives and friends, a portrait has its own rights as a picture, and this one certainly has. For a time McGlashan was kept uncomfortably busy. One of his commissions dragged him to a chateau on the Loire and the prospects of a career to be continued in America. The prospects did not appear to have any magnetic pull, for he suddenly became tired of the whole business and came back home to Glasgow. He may have been homesick. But I think it is more likely he was afraid he might lose his freedom. His convictions have always been strong and deep-seated. He has never allowed flattery or public acclamation to lead him away from his settled course. And he has now become one of out elder statesmen, so to speak. Having attained full academic honours, he continues to live and work in the first home he had in Glasgow. He married Therese Giuliani – member of a well-known Glasgow-Italian family. The babies they reared are children no more. The elder daughter studied Social Welfare at Glasgow University and has continued in London to take interest in a wider sphere of activity in the world of committees. Young John, after obtaining his diploma at the Glasgow School of Art, is now as a successful free-lance. He achieved the distinction of a scholarship awarded by Punch, to whose pages he has contributed. The younger daughter has also followed in her father’s footsteps to a diploma in art, and also, like him, has ventured into the fields of matrimony. The children have now contributed two grandchildren to the McGlashan family. We keep on harping on babies, but it would be a disservice to Archibald McGlashan not to mention the flower paintings and the still-life themes to which he frequently returns. His signature is unmistakable, s is the occasional butterfly, which, unlike Whistler’s, has no sting in its tail. But it is the babies, in their cots or in their prams, or on their mothers’ knees, their eyes closed or wide open, who convey the conviction: “The man who has done this must have found great joy in the doing of it”.

|